...ocupo Reef Salt de Seachem...no he medido los TDS del Ro (pero no creo que vaya por ahi el problema, es un equipo nuevo)....estoy en eso ...cambios constantes de agua...Tanoman escribió:ANZUMI escribió: NO3 100 mg/l

viejo como maximo los nitratos deberian ser 50 (en el test sera), pero en realidad deberian ser maximo 20!!1

y pa SPS maximo 5-10.

Asi que tienes un gran gran problema de nitratos. Hartos cambios de agua nomas hasta que te bajen!!

Que sal usas?

has medido los TDS de tu RO?

Duda con RDSB

Moderadores: Mava, GmoAndres, Thor, rmajluf, Kelthuzar

- ANZUMI

- Nivel 5

- Mensajes: 747

- Registrado: Vie, 13 Ene 2006, 09:22

- Sexo: Hombre

- Ubicación: Maipu, Santiago

Re: Duda con RDSB

- RAY

- Nivel 5

- Mensajes: 692

- Registrado: Mié, 21 Sep 2005, 20:33

- Ubicación: Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun

Re: Duda con RDSB

ANZUMI escribió: NO3 100 mg/l

NO2-N 0.3 mg/l

NO2 0.9 mg/l .

Densidad 1026

PH 8.3

KH 10dkh

...el dia sabado al revisar el sump para limpiar el skimmer , encontré una damisela (que tenia separada para regalar) muerta (me imagino que hace un par de dias por su estado de descomposicion).

esa es la causa de tus nitratos .

Re: Duda con RDSB

hola T2

bueno vayamos por partes a fin de aclarar ciertos comentarios y dudas al respecto al uso del RDSB y AZNO3.

aunque hay varios comentarios en favor de utilizar en la cama de arena se puede utilizar desde arena silica, aragonita, coral licuado siempre y cuando la granulometria se encuentre entre 1-2mm.

en un RDSD la altura de la arena debe de ser de 25 cm, y no debe de llevar absolutamente NADA de luz.

Calfo menciona lo siguiente:

to adequately denitrify ~ 300 gallons of system water with a typical bioload, you will need to fill a 20 gallon compartment (volumetrically) with fine sand (under 2 mm grains... better still if under 1 mm IMO). Thats the rough equivilent of 160-180 lbs (or three 5 gallon buckets) of "sugar fine" sand to get significant nitrate reduction via a RDSB

=================================================================================================

Para bajar nitratos de aproximadamente 1000 litros con una carga tipica vas a necesitar llenar un recipiente de un volumen aprox. de 75-80 lts. con arena fina (menor de 2 mm... mejor todavia mejor de 1 mm.). Esto es a grosso modo equivalente a 70-80 kgs. de arena -o 3 recipientes de unos 5 galones) de arena de grano "azucar" para lograr una reduccion de nitratos via RDSB.

La explicacion del porque la tiene en alguna parte que he leido y es porque el menor espacio entre los granos de arena impide que las particulas de material organico (solidos) se filtren y se metan en la arena.

With proper waterflow and (solids) nutrient export at large, there just isn't enough matter to sink and begin to accumulate. And the fine sand (<1mm) in particular does not allow the penetration but rather deflects large solids for them to carry on with currents and stay (properly) in suspension long(er) enough for filter feeders to utilize them or skimmers/filters to simply export or trap them.

==================================================================================================

Con circulacion apropiada y buena exportacion de nutrientes no habria suficiente cantidad de materia que se hunda y comience a acumularse. Y la arena fina (< 1mm) en particular no permite la penetracion sino que mas bien desvia los solidos grandes que traiga el flujo y los mantiene en suspension mas tiempo para que los organismos filtrantes los utilicen o los skimmers/filtros simplemente los atrapen.

Por otro lado, la función de la granulometría fina no es solo la de evitar la entrada de residuos en el interior de la cama, sino la de ofrecer una mayor superficie de asiento bacterial, que con granulometrías gruesas disminuyes drásticamente

bueno vayamos por partes a fin de aclarar ciertos comentarios y dudas al respecto al uso del RDSB y AZNO3.

aunque hay varios comentarios en favor de utilizar en la cama de arena se puede utilizar desde arena silica, aragonita, coral licuado siempre y cuando la granulometria se encuentre entre 1-2mm.

en un RDSD la altura de la arena debe de ser de 25 cm, y no debe de llevar absolutamente NADA de luz.

Calfo menciona lo siguiente:

to adequately denitrify ~ 300 gallons of system water with a typical bioload, you will need to fill a 20 gallon compartment (volumetrically) with fine sand (under 2 mm grains... better still if under 1 mm IMO). Thats the rough equivilent of 160-180 lbs (or three 5 gallon buckets) of "sugar fine" sand to get significant nitrate reduction via a RDSB

=================================================================================================

Para bajar nitratos de aproximadamente 1000 litros con una carga tipica vas a necesitar llenar un recipiente de un volumen aprox. de 75-80 lts. con arena fina (menor de 2 mm... mejor todavia mejor de 1 mm.). Esto es a grosso modo equivalente a 70-80 kgs. de arena -o 3 recipientes de unos 5 galones) de arena de grano "azucar" para lograr una reduccion de nitratos via RDSB.

La explicacion del porque la tiene en alguna parte que he leido y es porque el menor espacio entre los granos de arena impide que las particulas de material organico (solidos) se filtren y se metan en la arena.

With proper waterflow and (solids) nutrient export at large, there just isn't enough matter to sink and begin to accumulate. And the fine sand (<1mm) in particular does not allow the penetration but rather deflects large solids for them to carry on with currents and stay (properly) in suspension long(er) enough for filter feeders to utilize them or skimmers/filters to simply export or trap them.

==================================================================================================

Con circulacion apropiada y buena exportacion de nutrientes no habria suficiente cantidad de materia que se hunda y comience a acumularse. Y la arena fina (< 1mm) en particular no permite la penetracion sino que mas bien desvia los solidos grandes que traiga el flujo y los mantiene en suspension mas tiempo para que los organismos filtrantes los utilicen o los skimmers/filtros simplemente los atrapen.

Por otro lado, la función de la granulometría fina no es solo la de evitar la entrada de residuos en el interior de la cama, sino la de ofrecer una mayor superficie de asiento bacterial, que con granulometrías gruesas disminuyes drásticamente

- ANZUMI

- Nivel 5

- Mensajes: 747

- Registrado: Vie, 13 Ene 2006, 09:22

- Sexo: Hombre

- Ubicación: Maipu, Santiago

Re: Duda con RDSB

Hace 2 dias volví a cambiar 40 lts. de agua y he notado una mejoria en los parametros:

NO3 25 Mg/lt

NO2 0 Mg/lt

KH dkh 12

PH 8.3

Densidad 1026

Aun estan los corales resentidos, espero que pronto empiecen a tirar para arriba. Haré otro cambio de agua este fin de semana, hasta quedar con los nitratos en 0.

NO3 25 Mg/lt

NO2 0 Mg/lt

KH dkh 12

PH 8.3

Densidad 1026

Aun estan los corales resentidos, espero que pronto empiecen a tirar para arriba. Haré otro cambio de agua este fin de semana, hasta quedar con los nitratos en 0.

Re: Duda con RDSB

Me da la impresión que escribiste mal el valor de los NO2.

Los nitratos en 0 no tiene que ser tu objetivo... trata de llegar a 10, y ya no deberías tener más problemas.

Saludos!

Yo

Los nitratos en 0 no tiene que ser tu objetivo... trata de llegar a 10, y ya no deberías tener más problemas.

Saludos!

Yo

- ANZUMI

- Nivel 5

- Mensajes: 747

- Registrado: Vie, 13 Ene 2006, 09:22

- Sexo: Hombre

- Ubicación: Maipu, Santiago

Re: Duda con RDSB

...exacto los nitritos en cero...corregidoDaniel escribió:Me da la impresión que escribiste mal el valor de los NO2.

Los nitratos en 0 no tiene que ser tu objetivo... trata de llegar a 10, y ya no deberías tener más problemas.

Saludos!

Yo

Gracias

Re: Duda con RDSB

desconozco el motivo por que salio el anterior post recortado, sin embargo continuo....

R. Shimek apunta los siguiente:

Sedimentos y Agua

Tanto en el arrecife real como en el acuario hay algunos aspectos de los sedimentos y el agua que son importantes. Primero, es importante reconocer que el movimiento pasivo del agua a través del sedimento es esencialmente imposible. Los canales entre los granos de arena son tan pequeños que la resistencia pasiva al movimiento pasivo del agua es para todo propósito práctico, absoluta. A menos que el agua se bombée a través del sedimento, simplemente no se moverá. Contrario a la mitología del acuario de arrecife, el agua no se "difunde" a través del sedimento. Los materiales disueltos en el agua se pueden difundir dentro del medio acuático, pero ese movimiento es muy lento y generalmente inconsecuente. Como veremos, a menos que el acuarista arregle algún tipo de bombeo activo, todo el movimiento de agua en el sedimento es mediado por los organismos.

El flujo de agua sobre los sedimentos puede ser turbulento, como el causado por una cabeza de poder, o laminar, como el causado por el movimiento de agua en conjunto. El flujo turbulento moverá algo de agua a través de las fracciones superiores de unos pocos centímetros del sedimento, el flujo laminar no. Sin embargo, en cualquier caso, habrá un poco de intercambio real de agua desde los intersticios del sedimento a la columna de agua y visceversa. Aún en acuarios con generadores de olas fuertes, mientras que el sedimento no sea movido físicamente, habrá poca mezcla entre el agua en el sedimento y el cuerpo de agua sobre el sedimento.

Esta division de agua en el acuario en dos cuerpos discretos de agua, la masa de agua sobre los sedimentos y la masa de agua en los sedimentos es muy importante para la funcionalidad de las camas de arena y el acuario. En la presencia de bacterias, resulta en la formación de capas relativamente discretas en los sedimentos basadas en la difusión de gases a través de la masa de agua del sedimento. Estas capas están caracterizadas generalmente por la concentración de oxígeno en el agua y se clasifican como aeróbicas, anaeróbicas y anóxicas. Las capas aeróbicas tienen concentraciones de oxígeno cercanas o iguales a las halladas en el agua que fluye sobre los sedimentos. Las capas anaeróbicas tienen algo de oxígeno presente, pero la concentración es menor que aquella en el agua sobre ellas. Las capas anóxicas no tienen oxígeno libre disuelto, y pueden ser llamadas capas reductoras, en contraste con las capas oxidantes.

Si no hubiese vida en los sedimentos, no habria capas. Las capas son generadas por la acción de las bacterias, microorganismos y animales que viven sobre la superficie de las partículas del sedimento y entre los granos del sedimento. Conforme estos organismos metabolizan, utilizan el oxígeno disponible. Todo el oxígeno en el sedimento es consumido relativamente rápido, resultando en capas anóxicas, donde la única vida es bacteriana. El oxígeno se difunde en los sedimentos desde las capas de agua sobre ellos, pero esa difusión es muy lenta. En la ausencia de animales en los sedimentos, las capas aeróbica y anaeróbica serían de sólo unas centésimas de centímetro de espesor y las capas anóxicas efectivamente se extenderían hasta la superficie.

inclusive a diferentes tamaños de la arena siempre y cuando no sobrepasen los 2mm las puedes poner en cualquier forma, es decir la de menor tamaño por debajo de la más grande.

R. Shimek apunta los siguiente:

Sedimentos y Agua

Tanto en el arrecife real como en el acuario hay algunos aspectos de los sedimentos y el agua que son importantes. Primero, es importante reconocer que el movimiento pasivo del agua a través del sedimento es esencialmente imposible. Los canales entre los granos de arena son tan pequeños que la resistencia pasiva al movimiento pasivo del agua es para todo propósito práctico, absoluta. A menos que el agua se bombée a través del sedimento, simplemente no se moverá. Contrario a la mitología del acuario de arrecife, el agua no se "difunde" a través del sedimento. Los materiales disueltos en el agua se pueden difundir dentro del medio acuático, pero ese movimiento es muy lento y generalmente inconsecuente. Como veremos, a menos que el acuarista arregle algún tipo de bombeo activo, todo el movimiento de agua en el sedimento es mediado por los organismos.

El flujo de agua sobre los sedimentos puede ser turbulento, como el causado por una cabeza de poder, o laminar, como el causado por el movimiento de agua en conjunto. El flujo turbulento moverá algo de agua a través de las fracciones superiores de unos pocos centímetros del sedimento, el flujo laminar no. Sin embargo, en cualquier caso, habrá un poco de intercambio real de agua desde los intersticios del sedimento a la columna de agua y visceversa. Aún en acuarios con generadores de olas fuertes, mientras que el sedimento no sea movido físicamente, habrá poca mezcla entre el agua en el sedimento y el cuerpo de agua sobre el sedimento.

Esta division de agua en el acuario en dos cuerpos discretos de agua, la masa de agua sobre los sedimentos y la masa de agua en los sedimentos es muy importante para la funcionalidad de las camas de arena y el acuario. En la presencia de bacterias, resulta en la formación de capas relativamente discretas en los sedimentos basadas en la difusión de gases a través de la masa de agua del sedimento. Estas capas están caracterizadas generalmente por la concentración de oxígeno en el agua y se clasifican como aeróbicas, anaeróbicas y anóxicas. Las capas aeróbicas tienen concentraciones de oxígeno cercanas o iguales a las halladas en el agua que fluye sobre los sedimentos. Las capas anaeróbicas tienen algo de oxígeno presente, pero la concentración es menor que aquella en el agua sobre ellas. Las capas anóxicas no tienen oxígeno libre disuelto, y pueden ser llamadas capas reductoras, en contraste con las capas oxidantes.

Si no hubiese vida en los sedimentos, no habria capas. Las capas son generadas por la acción de las bacterias, microorganismos y animales que viven sobre la superficie de las partículas del sedimento y entre los granos del sedimento. Conforme estos organismos metabolizan, utilizan el oxígeno disponible. Todo el oxígeno en el sedimento es consumido relativamente rápido, resultando en capas anóxicas, donde la única vida es bacteriana. El oxígeno se difunde en los sedimentos desde las capas de agua sobre ellos, pero esa difusión es muy lenta. En la ausencia de animales en los sedimentos, las capas aeróbica y anaeróbica serían de sólo unas centésimas de centímetro de espesor y las capas anóxicas efectivamente se extenderían hasta la superficie.

inclusive a diferentes tamaños de la arena siempre y cuando no sobrepasen los 2mm las puedes poner en cualquier forma, es decir la de menor tamaño por debajo de la más grande.

Re: Duda con RDSB

bueno éste es el articulo de Anthony Calfo, por desgracia se encuentra en ingles, sin embargo, tal vez con la ayuda de un traductor podamos esclareser algunas dudas.

DSB - Deep Sand Bed Potential

Anthony Calfo

For many years, we have seen the use of substrates in marine aquaria wax and wane in popularity. The issue has run the gamut from bare bottom through shallow bed to deep sand, and then back to bare bottom again. But even with the acceptance of truly deep sand beds in America by the mid 1990’s, DSBs did not see regular use until refugia were established some years later. The reasons are obvious, perhaps: refugia are smaller, more affordable and less risky “models” of deep substrates, which the average hobbyist can attempt with greater confidence. But even with fears aside, the addition of a deep sand bed to a full display (versus a small refugium) is an investment in labor and money. It is no wonder that the large-scale DSBs took some time to be accepted.

As the popularity of DSBs grew, the number of critics did too. Sadly, many of the most outspoken detractors argued in theory without even trying a DSB! And the majority of the rest of the critics seemed to unfairly blame their aquarium failures on their very limited DSB experiences. The more likely cause of their failures was from typical bio-overloads, poor water flow, and neglect of water quality.

The reality of successful DSP applications, however, is amazingly simple, albeit strict. For perspective, I can tell you that my experience with living substrates is not insignificant. I utilized 48,000 lbs (over 20,000 kg!) of fine sand for my coral farming greenhouse operation and have installed similar deep sand beds in over one hundred private aquariums for over ten years. In this article, I will share with you a very practical survey of the potential - and the limitations - of a deep sand bed application.

If I had to reduce the summary of challenges of deep sand bed applications to a single statement, I would have to say that new hobbyists have unrealistic expectations for what a deep sand bed can do. That is not to say that a deep sand bed does not have great potential! They truly do. But many people seem to have extremely high expectations for new sand to become teeming with life almost overnight in aquaria. Such a thing is difficult and requires careful orchestration, time and patience to happen. But more often, it fails because of impatience; aquarists stock DSB aquariums too quickly with predatory fishes that consume the foundling populations of desirable worms, microcrustaceans and other sand fauna, before the sand life can adequately populate to sustain predation. That is an enormous mistake. The inferior biotic faculties struggle to process the all-too-common overload of fishes, food and waste in aquaria, and the DSB fails in such circumstances.

A similar problem occurs in DSB systems with inadequate water movement that allows too much particulate waste to sink and accumulate excessively in the DSB over time, causing the aquarium to “crash.” Instead, we should aspire (in bare bottom and DSB aquaria alike!) to always keep reef-like water movement with strong flow that keeps solid matter in suspension longer for greater feeding opportunities by the filter feeders and better processing by skimmers and other filters. Strong water movement in the aquarium is the number one key to success with long-term healthy DSBs. I recommend “sps-style” water flow of near 40-60 X turnover of the tank display for best results.

I can remember in the early days of reef-keeping in America, we would hear stories of great German aquarists that would keep their new live rock (for “Berlin” style systems) in the dark for six months or more with good water flow and supplementation (organic and inorganic). The purpose was to dramatically improve the quality of “cured” live rock with greater coralline algae and more life forms before lights and fishes were applied. Few American aquarists had the patience to do this at the time, but I think we must have admired the German stony coral displays so much and remembered the lesson that we apply it now to our refugia and DSBs. Now, with thanks and respect, we remind our European friends of this same patient advice: avoid adding predatory fishes or corals to DSB systems for many months to allow adequate populations of infauna to develop.

You will notice that these two fundamental pieces of advice are different from what most retailers and so-called experts will recommend. Both mistakenly tell you to add “clean up” organisms from the very beginning (note: at least one of those two people profit from this bad advice ). But the addition of predatory snails such as Whelk (Buccinid), Murex (Muricid), Mud (Nassarid) and Tulip (Fasciolariid) can be devastating to the desirable life forms in the sand of an aquarium. The popular Conch species (Strombids) are even worse as most will starve to death not long after they have decimated the infauna of a DSB. Of similar concern is the use of Holothurid “Sea cucumbers” (and Sand-dollars) and all of the sand-sifting gobies. These vigorous sifters destroy a lot of biomass in the substrate. Worst of all perhaps are the alleged “reef-safe” hermit crabs; these crabs are brutally indiscriminate predators on desirable sand bed life forms. The only thing that any of these aforementioned “bad” DSB organisms are actually good for is tilling the sand surface to prevent the buildup of brown diatom algae. But you can use a number of safer organisms to accomplish algae control without destroying DSB biodiversity!

Best bets for DSBs include: Stomatella-type “paper shell” snails, Ceriths (Cerithium and close kin) and most all errantiate polychate worms. Yes… “bristleworms” are very good. They are rate-limited in population by available food, which in turn is rate-limited by good water flow that prevents excessive solid matter from settling and accumulating over time (back to rule #1 above regarding adequate water flow). In time, you may even allow small Asterina-type sea stars to flourish (this is somewhat controversial, but they are generally harmless, if not helpful). For starfish, Ophiuroid species (Brittle or Serpent starfish) are perhaps best of all for being low burden, low maintenance and high utility as scavengers. After a year of establishment, various ornamental shrimps, such as Lysmata, may also be added; their benefit (producing larvae as food for corals) may balance with their burden (preying on DSB fauna). And for fishes, perhaps the best “clean up” group is the bristle-tooth tangs of the genus Ctenochaetus with their specialized mouthparts that comb diatom algae from the soft sand with little burden otherwise on desirable sand fauna. Manual sand stirring by the aquarist, though, is not needed when adequate water flow and livestock are in place. That said, manual stirring can be helpful for feeding some specialized filter feeders or extending the life of the sand bed when water flow is not ideal in support.

In time, you will see various colored algae appear to grow substratum, but they are only existing in tiny films between the aquarium glass and the sand face; they are not growing throughout the sand bed. Such algae are often stimulated to grow in front because of the indirect room light and the aquarium lights reflected down through the vertical panes of the aquarium. Many aquarists with adequate water flow and good DSB maintenance have also noticed that while moving an established sand bed, the overall substrate is remarkably clean and odor free like the first day it was placed into the aquarium! This is exactly how a healthy DSB should be after many years. I personally moved a nine-year old sand bed (15 cm deep in a 1000 liter aquarium that held two small reef sharks) that made this very same impression on me: clean, odorless, healthy living sand.

Perhaps the most underrated but also the most reliable and significant benefit to a DSB is the ability to reduce nitrates naturally and quickly. Over ten years ago I wrote about hobbyists using a remote DSB (AKA – “RDSB”) as a means of addressing the fears that many folks had at the time (and some still do) about “what if” a display DSB gets polluted or goes bad. It is true too; illuminated DSBs are more of a challenge to keep healthy because of the site competition (sand surface) between desirable and undesirable life forms with the increased availability of energy sources (food, waste, light). Yet, most all of the benefits of a DSB can be had with an unlit DSB reservoir that is plumbed inline to the main system. The typical RDSB application for home-sized aquariums (under 800 liters) is a large bucket full of sand (maybe 25 kg of fine sand in a 20 liter bucket) that has a supply of filtered water on a continuing path in the aquarium system. Some folks simplify it even further by sitting their RDSB bucket in an unlit sump and gravity feed water from a display or refugium above… or even a tee off of the sump pump manifold. The sump RDSB can then gently spill over the sides of the bucket into the open reservoir. It is quite simple and effective for mainataining nitrates below 10 ppm.

However you choose to install an inline (R)DSB, you can estimate that approximately 25 kg of fine sand (< 2mm grain size) per 400 liters of aquarium water will fully, or nearly so, reduce nitrates in a typical bioload. For over a decade, aquarists at large have reported struggles to keep nitrate levels under 40ppm with large and frequent water changes and other drastic measures to no avail. But, after the installation of an RDSB, nitrates were reduced in less than 4 months with many showing significant progress in 8 weeks or less. I have even observed several retail stores with heavy bioloads in central filtration systems see their nitrates reduced to near zero with the installation of a sand-filled 200 liter RDSB aquarium (1mm sand grain size… full nearly to the top with only 10 cm of water flowing across the sand surface). This is effective on 4000 liter fish holding systems! The single greatest benefit of a DSB is nitrate control. While many aquarists like to claim through the years that higher nitrates are tolerated by many fishes, the reality is that many other fishes do not tolerate it well. Reports about Pterois, Sharks and other predators, for example, implicate high nitrate levels as inhibitory to iodine uptake, which can lead then to thyroid hyperplasia (“goiter” in the throat). The condition worsens in time to the point where the animal is unable to feed.

Using the bucket RDSB as an example (versus refugium substrates or display DSBs), this is perhaps an illustration of all of the best and worst of a DSB application:

There is little risk and little gain (aside from great nitrate control) to healthy DSBs

Strong water flow above a DSB will easily keep it healthy, poor water flow will quickly destroy it

Anywhere you choose to install a DSB is simple and inexpensive, but laborious and cumbersome (space-consuming)

Living sand is like living rock: great patience produces superb quality living substrates, but impatience (stocking with fishes/corals too soon) produces worthless living substrates

One of the great advantages to having your DSB remote in refugia or a bucket is that it can be turned offline or bypassed rather easily if special needs call for it. Medicating the main display can be difficult or practically impossible with an in-tank deep substrate that absorbs medication and kills off a massive amount of infauana. But a remote DSB can run fallow on a small loop of recirculating water while the needs of the display are addressed in cases of emergency. If the RDSB fails for any reason likewise, its removal from the system can be a simple valve turn away versus an enormous project of draining a tank for display DSBs. My recommendation is most always to keep your DSB remotely for these reasons and more.

We must also consider the composition of sand used for DSB to support desirable life forms in and above the substrate as well as be supported by applied water flow. The “rules” for DSB sand are not very strict, but they are rather practical. When our stated goals are culturing low-oxygen faculties for nitrate reduction plus the minimal penetration of and accumulation of solids in the substrate over time, smaller sand grains are better suited for the purpose. I recommend sand grains under 2 mm in size for DSBs. Media that is larger than 2 mm can be used, but deeper beds and stronger water flow will be required to make it work successfully. Large sand grains allow excessive solid matter to penetrate deeper and faster and can lead to the problem that critics cite with DSBs becoming “nutrient sinks.” That said, a mix of large and fine grain sizes together can work if there is enough fine sand (< 2 mm) to fill the interstices. It is arguably better to mix DSB sands for greater biodiversity of infauna whereas a uniform grain size favors the dominant growth of certain organisms over others.

Lastly, there has been a bit too much debate, in my opinion, over the intrinsic composition of DSB sands. The three principal choices are calcite, silica or aragonite. Each media type has its fans and critics alike. All, I assure you, can be quite similarly useful without nearly the difference in performance that the critics would lead you to believe. The fundamental thing to search for with any of them is grain size as per above, without much concern for chemical makeup. The advantages and disadvantages of each class of sand are as follows:

Calcite DSB

advantages: commonly available, moderately priced, wide range of grain sizes

disadvantages: very little buffering ability over 7.6 pH

Silica DSB

advantages: very inexpensive from industrial sources

disadvantages: no buffering, limited sizes (<1 mm), poor shapes (sharp and lacking fluidity)

Aragonite DSB

advantage: optimal shapes (oolitic and very fluid), excellent buffering pH, and mineral supplying

disadvantage: generally more expensive and less available than silica or calcite

Depending on aquarists’ budgets and access to choices among sand substrates, each composition listed above can be used and finessed appropriately. The oolitic (round/spheres) shape of aragonite affords the most fluid DSB that naturally churns and feeds lower zones while reducing diatom growth at the surface. Silica sand, on the contrary, locks its sharp grains and packs with very little movement. As such, solid waste is less likely to penetrate, for better and for worse (less food for biotic faculties), while diatoms can grow more easily at the surface. A silica DSB will be less expensive to install but more expensive (labor) to maintain… perhaps requiring manual sand stirring and greater water flow. Aquarium hobbyists usually find calcite sand beds to be the best choice for aesthetics, price, availability and required husbandry; all are moderate.

With this primer, I hope to have provided you with a “noiseless” summary of the legitimate and practical expectations for what a DSB can – and cannot – do. If you can resist the extreme ends of the argument, I think you will find that this is a viable and reliable methodology for marine aquariums. With kind regards

DSB - Deep Sand Bed Potential

Anthony Calfo

For many years, we have seen the use of substrates in marine aquaria wax and wane in popularity. The issue has run the gamut from bare bottom through shallow bed to deep sand, and then back to bare bottom again. But even with the acceptance of truly deep sand beds in America by the mid 1990’s, DSBs did not see regular use until refugia were established some years later. The reasons are obvious, perhaps: refugia are smaller, more affordable and less risky “models” of deep substrates, which the average hobbyist can attempt with greater confidence. But even with fears aside, the addition of a deep sand bed to a full display (versus a small refugium) is an investment in labor and money. It is no wonder that the large-scale DSBs took some time to be accepted.

As the popularity of DSBs grew, the number of critics did too. Sadly, many of the most outspoken detractors argued in theory without even trying a DSB! And the majority of the rest of the critics seemed to unfairly blame their aquarium failures on their very limited DSB experiences. The more likely cause of their failures was from typical bio-overloads, poor water flow, and neglect of water quality.

The reality of successful DSP applications, however, is amazingly simple, albeit strict. For perspective, I can tell you that my experience with living substrates is not insignificant. I utilized 48,000 lbs (over 20,000 kg!) of fine sand for my coral farming greenhouse operation and have installed similar deep sand beds in over one hundred private aquariums for over ten years. In this article, I will share with you a very practical survey of the potential - and the limitations - of a deep sand bed application.

If I had to reduce the summary of challenges of deep sand bed applications to a single statement, I would have to say that new hobbyists have unrealistic expectations for what a deep sand bed can do. That is not to say that a deep sand bed does not have great potential! They truly do. But many people seem to have extremely high expectations for new sand to become teeming with life almost overnight in aquaria. Such a thing is difficult and requires careful orchestration, time and patience to happen. But more often, it fails because of impatience; aquarists stock DSB aquariums too quickly with predatory fishes that consume the foundling populations of desirable worms, microcrustaceans and other sand fauna, before the sand life can adequately populate to sustain predation. That is an enormous mistake. The inferior biotic faculties struggle to process the all-too-common overload of fishes, food and waste in aquaria, and the DSB fails in such circumstances.

A similar problem occurs in DSB systems with inadequate water movement that allows too much particulate waste to sink and accumulate excessively in the DSB over time, causing the aquarium to “crash.” Instead, we should aspire (in bare bottom and DSB aquaria alike!) to always keep reef-like water movement with strong flow that keeps solid matter in suspension longer for greater feeding opportunities by the filter feeders and better processing by skimmers and other filters. Strong water movement in the aquarium is the number one key to success with long-term healthy DSBs. I recommend “sps-style” water flow of near 40-60 X turnover of the tank display for best results.

I can remember in the early days of reef-keeping in America, we would hear stories of great German aquarists that would keep their new live rock (for “Berlin” style systems) in the dark for six months or more with good water flow and supplementation (organic and inorganic). The purpose was to dramatically improve the quality of “cured” live rock with greater coralline algae and more life forms before lights and fishes were applied. Few American aquarists had the patience to do this at the time, but I think we must have admired the German stony coral displays so much and remembered the lesson that we apply it now to our refugia and DSBs. Now, with thanks and respect, we remind our European friends of this same patient advice: avoid adding predatory fishes or corals to DSB systems for many months to allow adequate populations of infauna to develop.

You will notice that these two fundamental pieces of advice are different from what most retailers and so-called experts will recommend. Both mistakenly tell you to add “clean up” organisms from the very beginning (note: at least one of those two people profit from this bad advice ). But the addition of predatory snails such as Whelk (Buccinid), Murex (Muricid), Mud (Nassarid) and Tulip (Fasciolariid) can be devastating to the desirable life forms in the sand of an aquarium. The popular Conch species (Strombids) are even worse as most will starve to death not long after they have decimated the infauna of a DSB. Of similar concern is the use of Holothurid “Sea cucumbers” (and Sand-dollars) and all of the sand-sifting gobies. These vigorous sifters destroy a lot of biomass in the substrate. Worst of all perhaps are the alleged “reef-safe” hermit crabs; these crabs are brutally indiscriminate predators on desirable sand bed life forms. The only thing that any of these aforementioned “bad” DSB organisms are actually good for is tilling the sand surface to prevent the buildup of brown diatom algae. But you can use a number of safer organisms to accomplish algae control without destroying DSB biodiversity!

Best bets for DSBs include: Stomatella-type “paper shell” snails, Ceriths (Cerithium and close kin) and most all errantiate polychate worms. Yes… “bristleworms” are very good. They are rate-limited in population by available food, which in turn is rate-limited by good water flow that prevents excessive solid matter from settling and accumulating over time (back to rule #1 above regarding adequate water flow). In time, you may even allow small Asterina-type sea stars to flourish (this is somewhat controversial, but they are generally harmless, if not helpful). For starfish, Ophiuroid species (Brittle or Serpent starfish) are perhaps best of all for being low burden, low maintenance and high utility as scavengers. After a year of establishment, various ornamental shrimps, such as Lysmata, may also be added; their benefit (producing larvae as food for corals) may balance with their burden (preying on DSB fauna). And for fishes, perhaps the best “clean up” group is the bristle-tooth tangs of the genus Ctenochaetus with their specialized mouthparts that comb diatom algae from the soft sand with little burden otherwise on desirable sand fauna. Manual sand stirring by the aquarist, though, is not needed when adequate water flow and livestock are in place. That said, manual stirring can be helpful for feeding some specialized filter feeders or extending the life of the sand bed when water flow is not ideal in support.

In time, you will see various colored algae appear to grow substratum, but they are only existing in tiny films between the aquarium glass and the sand face; they are not growing throughout the sand bed. Such algae are often stimulated to grow in front because of the indirect room light and the aquarium lights reflected down through the vertical panes of the aquarium. Many aquarists with adequate water flow and good DSB maintenance have also noticed that while moving an established sand bed, the overall substrate is remarkably clean and odor free like the first day it was placed into the aquarium! This is exactly how a healthy DSB should be after many years. I personally moved a nine-year old sand bed (15 cm deep in a 1000 liter aquarium that held two small reef sharks) that made this very same impression on me: clean, odorless, healthy living sand.

Perhaps the most underrated but also the most reliable and significant benefit to a DSB is the ability to reduce nitrates naturally and quickly. Over ten years ago I wrote about hobbyists using a remote DSB (AKA – “RDSB”) as a means of addressing the fears that many folks had at the time (and some still do) about “what if” a display DSB gets polluted or goes bad. It is true too; illuminated DSBs are more of a challenge to keep healthy because of the site competition (sand surface) between desirable and undesirable life forms with the increased availability of energy sources (food, waste, light). Yet, most all of the benefits of a DSB can be had with an unlit DSB reservoir that is plumbed inline to the main system. The typical RDSB application for home-sized aquariums (under 800 liters) is a large bucket full of sand (maybe 25 kg of fine sand in a 20 liter bucket) that has a supply of filtered water on a continuing path in the aquarium system. Some folks simplify it even further by sitting their RDSB bucket in an unlit sump and gravity feed water from a display or refugium above… or even a tee off of the sump pump manifold. The sump RDSB can then gently spill over the sides of the bucket into the open reservoir. It is quite simple and effective for mainataining nitrates below 10 ppm.

However you choose to install an inline (R)DSB, you can estimate that approximately 25 kg of fine sand (< 2mm grain size) per 400 liters of aquarium water will fully, or nearly so, reduce nitrates in a typical bioload. For over a decade, aquarists at large have reported struggles to keep nitrate levels under 40ppm with large and frequent water changes and other drastic measures to no avail. But, after the installation of an RDSB, nitrates were reduced in less than 4 months with many showing significant progress in 8 weeks or less. I have even observed several retail stores with heavy bioloads in central filtration systems see their nitrates reduced to near zero with the installation of a sand-filled 200 liter RDSB aquarium (1mm sand grain size… full nearly to the top with only 10 cm of water flowing across the sand surface). This is effective on 4000 liter fish holding systems! The single greatest benefit of a DSB is nitrate control. While many aquarists like to claim through the years that higher nitrates are tolerated by many fishes, the reality is that many other fishes do not tolerate it well. Reports about Pterois, Sharks and other predators, for example, implicate high nitrate levels as inhibitory to iodine uptake, which can lead then to thyroid hyperplasia (“goiter” in the throat). The condition worsens in time to the point where the animal is unable to feed.

Using the bucket RDSB as an example (versus refugium substrates or display DSBs), this is perhaps an illustration of all of the best and worst of a DSB application:

There is little risk and little gain (aside from great nitrate control) to healthy DSBs

Strong water flow above a DSB will easily keep it healthy, poor water flow will quickly destroy it

Anywhere you choose to install a DSB is simple and inexpensive, but laborious and cumbersome (space-consuming)

Living sand is like living rock: great patience produces superb quality living substrates, but impatience (stocking with fishes/corals too soon) produces worthless living substrates

One of the great advantages to having your DSB remote in refugia or a bucket is that it can be turned offline or bypassed rather easily if special needs call for it. Medicating the main display can be difficult or practically impossible with an in-tank deep substrate that absorbs medication and kills off a massive amount of infauana. But a remote DSB can run fallow on a small loop of recirculating water while the needs of the display are addressed in cases of emergency. If the RDSB fails for any reason likewise, its removal from the system can be a simple valve turn away versus an enormous project of draining a tank for display DSBs. My recommendation is most always to keep your DSB remotely for these reasons and more.

We must also consider the composition of sand used for DSB to support desirable life forms in and above the substrate as well as be supported by applied water flow. The “rules” for DSB sand are not very strict, but they are rather practical. When our stated goals are culturing low-oxygen faculties for nitrate reduction plus the minimal penetration of and accumulation of solids in the substrate over time, smaller sand grains are better suited for the purpose. I recommend sand grains under 2 mm in size for DSBs. Media that is larger than 2 mm can be used, but deeper beds and stronger water flow will be required to make it work successfully. Large sand grains allow excessive solid matter to penetrate deeper and faster and can lead to the problem that critics cite with DSBs becoming “nutrient sinks.” That said, a mix of large and fine grain sizes together can work if there is enough fine sand (< 2 mm) to fill the interstices. It is arguably better to mix DSB sands for greater biodiversity of infauna whereas a uniform grain size favors the dominant growth of certain organisms over others.

Lastly, there has been a bit too much debate, in my opinion, over the intrinsic composition of DSB sands. The three principal choices are calcite, silica or aragonite. Each media type has its fans and critics alike. All, I assure you, can be quite similarly useful without nearly the difference in performance that the critics would lead you to believe. The fundamental thing to search for with any of them is grain size as per above, without much concern for chemical makeup. The advantages and disadvantages of each class of sand are as follows:

Calcite DSB

advantages: commonly available, moderately priced, wide range of grain sizes

disadvantages: very little buffering ability over 7.6 pH

Silica DSB

advantages: very inexpensive from industrial sources

disadvantages: no buffering, limited sizes (<1 mm), poor shapes (sharp and lacking fluidity)

Aragonite DSB

advantage: optimal shapes (oolitic and very fluid), excellent buffering pH, and mineral supplying

disadvantage: generally more expensive and less available than silica or calcite

Depending on aquarists’ budgets and access to choices among sand substrates, each composition listed above can be used and finessed appropriately. The oolitic (round/spheres) shape of aragonite affords the most fluid DSB that naturally churns and feeds lower zones while reducing diatom growth at the surface. Silica sand, on the contrary, locks its sharp grains and packs with very little movement. As such, solid waste is less likely to penetrate, for better and for worse (less food for biotic faculties), while diatoms can grow more easily at the surface. A silica DSB will be less expensive to install but more expensive (labor) to maintain… perhaps requiring manual sand stirring and greater water flow. Aquarium hobbyists usually find calcite sand beds to be the best choice for aesthetics, price, availability and required husbandry; all are moderate.

With this primer, I hope to have provided you with a “noiseless” summary of the legitimate and practical expectations for what a DSB can – and cannot – do. If you can resist the extreme ends of the argument, I think you will find that this is a viable and reliable methodology for marine aquariums. With kind regards

Re: Duda con RDSB

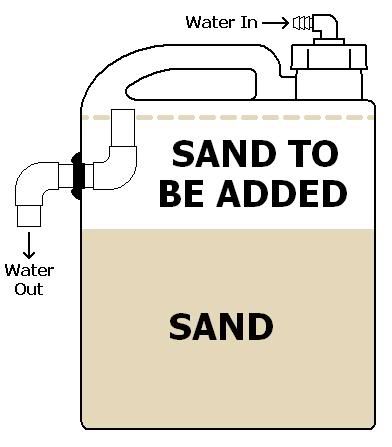

dicho de otra manera:

El sistema RDSB es en si un DSB remoto, es decir, la arena no se sitúa en el propio tanque sino en un recipiente aparte y pueden construirse a partir de depósitos plásticos cerrados, papeleras, bidones, etc. En estos RDSB no "sembraremos" nada de plantas ni animales y su misión será eliminar NO3 a partir de una cama profunda de arena. Para ello elegiremos depósitos altos que aseguren una proliferación de bacterias desnitrificantes en el fondo del mismo.

Los alimentaremos con agua exenta de restos orgánicos procedentes del acuario y tanto el agua de entrada como de salida al RDSB entrarán por arriba. La capa de agua ruperior será de unos pocos cm, 6 u 8.

La arena ideal es la aragonita en su grano más fino ya que además, ayudará a taponar el pH del agua de nuestro acuario. También podría valer arena de tipo silíceo.

El recipiente deberá tener unas características especiales que nos proporcionen las máximas prestaciones, por lo que nos decantaremos por aquellos que sean profundos de unos 30 cm y con una capacidad de unos 25l. Para un acuario de 400l bastará con unos 20l de arena y un caudal de 400l de agua. El resultado en cuestión de reducción de NO3 es asombroso.

El agua de llegada a un RDSB, debe estar sin restos de materia y si por casualidad llega algo, que la propia corriente lo arrastre y deje la superficie limpia.

Con un filtro exterior se puede hacer este tipo de filtro de arena, pero debes eliminar la bomba o hacerle una modificación según modelo.

Ten en cuenta que los filtros de botella tienen la entrada de agua por la parte inferior y la salida por la superior, esto indudablemente no valdría.

El fondo del recipiente donde se encuentre la arena debe estar en condiciones de ausencia de oxigeno, por lo que no puede circular agua a su través.

Te vale cualquier recipiente, incluso un bidón de plástico. Le taladras dos orificios por la parte superior (uno para la entrada de agua y otro para la salida) y listo.

Si el recipiente contiene 20 litros de arena, te puede eliminar totalmente los nitratos en un acuario de 400 l, aunque el acuario este cargadillo de bichos, mismo que podrás realizar también de esta manera.

bucket y arena

conexión a cabeza de poder

perforaciones

coples de PVC a cubeta o bidon

verificando fugas

drenando y limpiando la arena

para mejores resultados las conexiones se suguiere utilizar el PVC para la salida

incorporando el bidon

ojala y con todo esto aclare algunas dudas.

El sistema RDSB es en si un DSB remoto, es decir, la arena no se sitúa en el propio tanque sino en un recipiente aparte y pueden construirse a partir de depósitos plásticos cerrados, papeleras, bidones, etc. En estos RDSB no "sembraremos" nada de plantas ni animales y su misión será eliminar NO3 a partir de una cama profunda de arena. Para ello elegiremos depósitos altos que aseguren una proliferación de bacterias desnitrificantes en el fondo del mismo.

Los alimentaremos con agua exenta de restos orgánicos procedentes del acuario y tanto el agua de entrada como de salida al RDSB entrarán por arriba. La capa de agua ruperior será de unos pocos cm, 6 u 8.

La arena ideal es la aragonita en su grano más fino ya que además, ayudará a taponar el pH del agua de nuestro acuario. También podría valer arena de tipo silíceo.

El recipiente deberá tener unas características especiales que nos proporcionen las máximas prestaciones, por lo que nos decantaremos por aquellos que sean profundos de unos 30 cm y con una capacidad de unos 25l. Para un acuario de 400l bastará con unos 20l de arena y un caudal de 400l de agua. El resultado en cuestión de reducción de NO3 es asombroso.

El agua de llegada a un RDSB, debe estar sin restos de materia y si por casualidad llega algo, que la propia corriente lo arrastre y deje la superficie limpia.

Con un filtro exterior se puede hacer este tipo de filtro de arena, pero debes eliminar la bomba o hacerle una modificación según modelo.

Ten en cuenta que los filtros de botella tienen la entrada de agua por la parte inferior y la salida por la superior, esto indudablemente no valdría.

El fondo del recipiente donde se encuentre la arena debe estar en condiciones de ausencia de oxigeno, por lo que no puede circular agua a su través.

Te vale cualquier recipiente, incluso un bidón de plástico. Le taladras dos orificios por la parte superior (uno para la entrada de agua y otro para la salida) y listo.

Si el recipiente contiene 20 litros de arena, te puede eliminar totalmente los nitratos en un acuario de 400 l, aunque el acuario este cargadillo de bichos, mismo que podrás realizar también de esta manera.

bucket y arena

conexión a cabeza de poder

perforaciones

coples de PVC a cubeta o bidon

verificando fugas

drenando y limpiando la arena

para mejores resultados las conexiones se suguiere utilizar el PVC para la salida

incorporando el bidon

ojala y con todo esto aclare algunas dudas.

Re: Duda con RDSB

hola y graciasTanoman escribió:Excelente muy clara la explicacion y el modelo a hacer!!

un RDSB es mejor que un refugio?

para tu servidor, son cosas diferentes con objetivos similares.

por un lado el refugio con el alga te absorberá igualmente el NO3 y al mismo tiempo los ortofosfatos, tal vez en mayor tiempo.

mientras que la cama remota al parecer solo los nitratos en forma mas biologica a través del proceso anaerobico y no estoy muy convencido que los PO4 los elimine.

hay muchos aficonados que tiene las 2 cosas.